French pastry for days

We’re in France! And we’re eating like we mean it.

Breakfast in Chartres

Baking in France is famously excellent but, less famously, unevenly so. Take pain au chocolat, for example. We’ve had some of these pastries that are almost intoxicating: golden, flaky, smelling of butter and the tang of melted dark chocolate. And sometimes we encounter chocolate croissants not worth eating: pale and compressed, gluey, with cold chocolate in two spartan batons.

A lovely street in Dinan

Apparently, young people in France no longer flock to professional baking. The work is hard, the mornings are early, the pay is little. So, in many places in France, chain bakeries have opened (we visited a Paul outlet in Chartres) and some independent shops use industrially produced and frozen croissants or pains au chocolat. The smallest towns are unable to sustain even these compromises and many are without bakeries. I read about a movement in recent years to create a network of bakeries in larger towns that supply small hamlets via depots de pain. As we drove through France from Chartres to Dinan, we saw automat-style kiosks on otherwise deserted main streets, filled each morning by a courier who drives, village to village, delivering daily bread.

The guys at Mont-Saint-Michel

The French government has also, bien sur, extended a helping hand to both eaters and traditional bakers by officially certifying quality: a baguette tradition must, by law, be baked on site, using traditional methods. And the government reserves a special designation, Boulanger de France, for bakeries where everything sold is produced by hand, on site, also using traditional methods.

Inside the abbey at Mont-Saint-Michel

Absent these formal designations, shoppers can avoid chain bakeries and shops where there is a dizzying variety; such a spread is generally not possible for smaller bakeries to achieve each day without resorting to industrial shortcuts. Finally, it’s instructive to look for a bit of unevenness in the shape of the breads and pastries as these are more likely to have been produced by hand rather than machine.

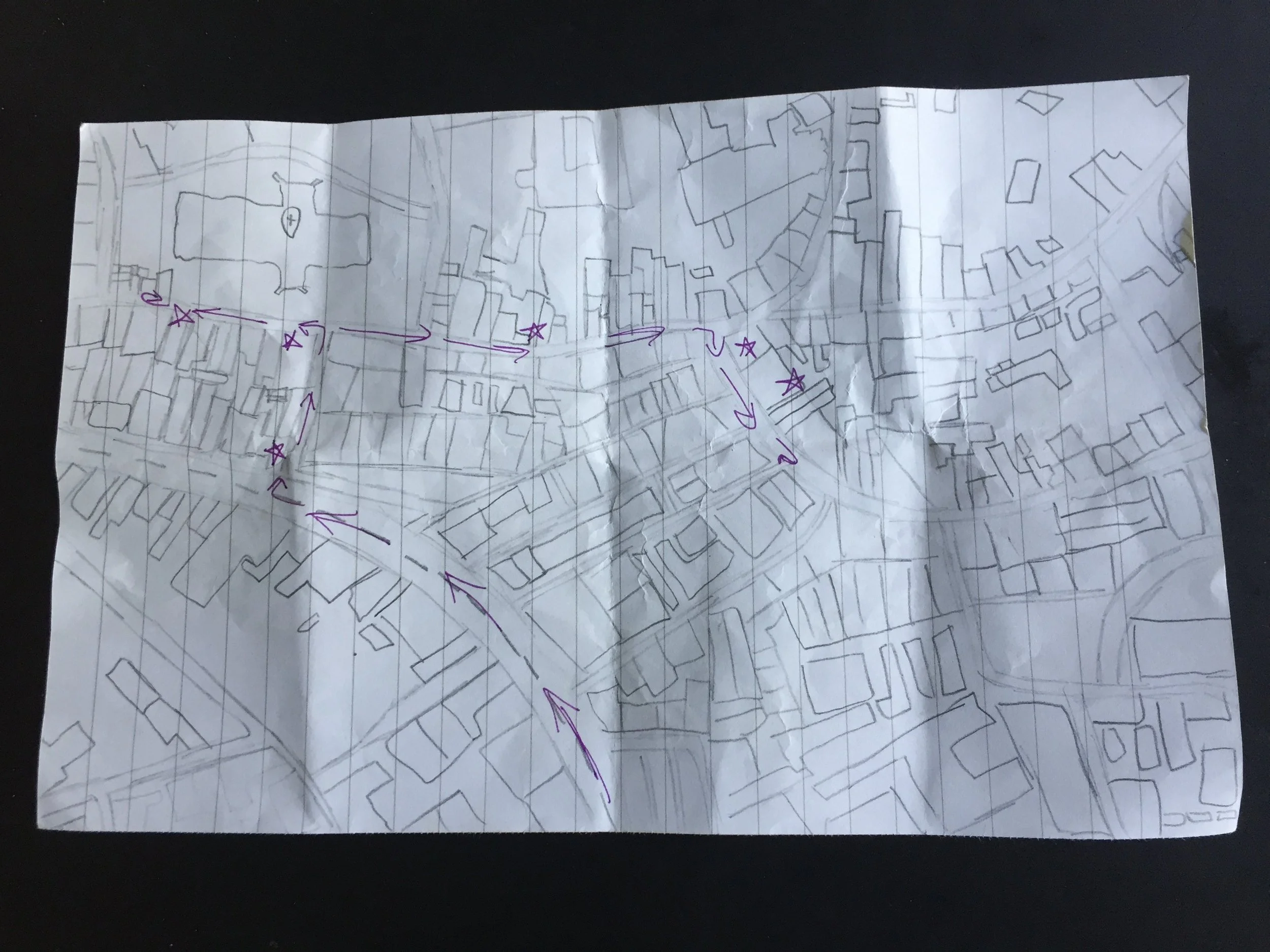

Joe’s map of bakery treasure in Dinan

So in the spirit of appreciation for traditional baking, we undertook a pain au chocolat project in Dinan. (Someone had to do it.) The guys led the charge: Sam researched available bakeries with promising reviews, then Joe created a map of six bakeries near our stone house just outside the old town walls. Thus armed, we set out one sunny afternoon, intending to try a pain au chocolat at each bakery, one after another. Choco-bang-bang!

Our first stop

Reader, we failed.

This one looks squished

Lamination!

That first afternoon, we made it through just two bakeries and the second was actually a Breton style place, offering regional treats like kouign-amann but no viennoise at all.

Get it?

We sat on the curb outside the second bakery, holding our bellies and groaning. Bang-bust! How did we think we could eat six pastries in a row?

Viewpoint behind Saint-Malo

Needing a break, we walked behind the old church to find a confusingly named jardin anglaise and a gorgeous viewpoint overlooking the river and lower neighborhoods of Dinan. Thus fortified, we tackled one additional bakery before packing it in for the day.

Meh. Or maybe it’s the third-pastry-effect

A few days later, we picked up the thread again and completed our six-bakery challenge. In the interim, I did a little reading and concluded that a certain bakery in the center of town, previously overlooked, might actually be our Holy Grail; its website advertised that all its products were produced on site, even the viennoise and patisserie. So we started there. I am happy to say L’Arome Sucre did not disappoint and became our go-to for baguette tradition for the remainder of our time in Dinan.

The clear winner

Notice how these croissants don’t all look identical

Perfection

Not a bad back-up

But none of the bakeries we visited in Dinan advertised the coveted Boulanger de France status and we wondered if maybe such an honor was mostly reserved for bakers in larger towns. The population of Dinan was around 11,000 in a recent census — maybe it’s a relative baking backwater? But a few days later, in Bayeux (population 13,000), we spotted the distinguished certificate, prominently displayed above the register in a bakery near our Airbnb.

France isn’t messing around

I promise you we ate everything there: baguette (three kinds), pain au chocolat, pain aux raisins, croissant aux amandes, something strangely called a pepino … we didn’t discriminate. Exactly none of it survived to be photographed, so you’ll have to trust me when I say that Monsieur Lepetit (HOW is that his name?) knows what he’s doing. And I sincerely hope he has several interns under his wing to supply France’s next generation of bakers.